Pro Bono, Jonathan Blitzer in The New Yorker:

When crises hit, the lawyers from Lone Star have answers to the overwhelming questions that follow the devastation: What if you lost your job because of the storm? (You have thirty days to file for unemployment.) How can you be sure that you’re not getting scammed by a contractor? (Ask to see his registration certificate with the Texas Residential Construction Commission.) How do you file claims with FEMA? (Very carefully.)

Roslyn Jackson, Lone Star’s supervising lawyer in Houston, was at home in Missouri City, twenty miles south, watching her yard fill up with water and texting her four managers. They were busy signing up staffers and volunteers for shifts at the shelters. “I’ve been through a lot of the high water, but nothing’s happened like this,” she said. “Employees kept calling to ask, ‘What can I do?’ We were getting texts until well after 2 A.M. I had to say, ‘All right, everybody, we got to go to bed. We start again at seven.’ ”

Access to Civil Justice: Keeping America's Promise

By Ronald S. Flagg, Vice President and General Counsel, Legal Services Corporation

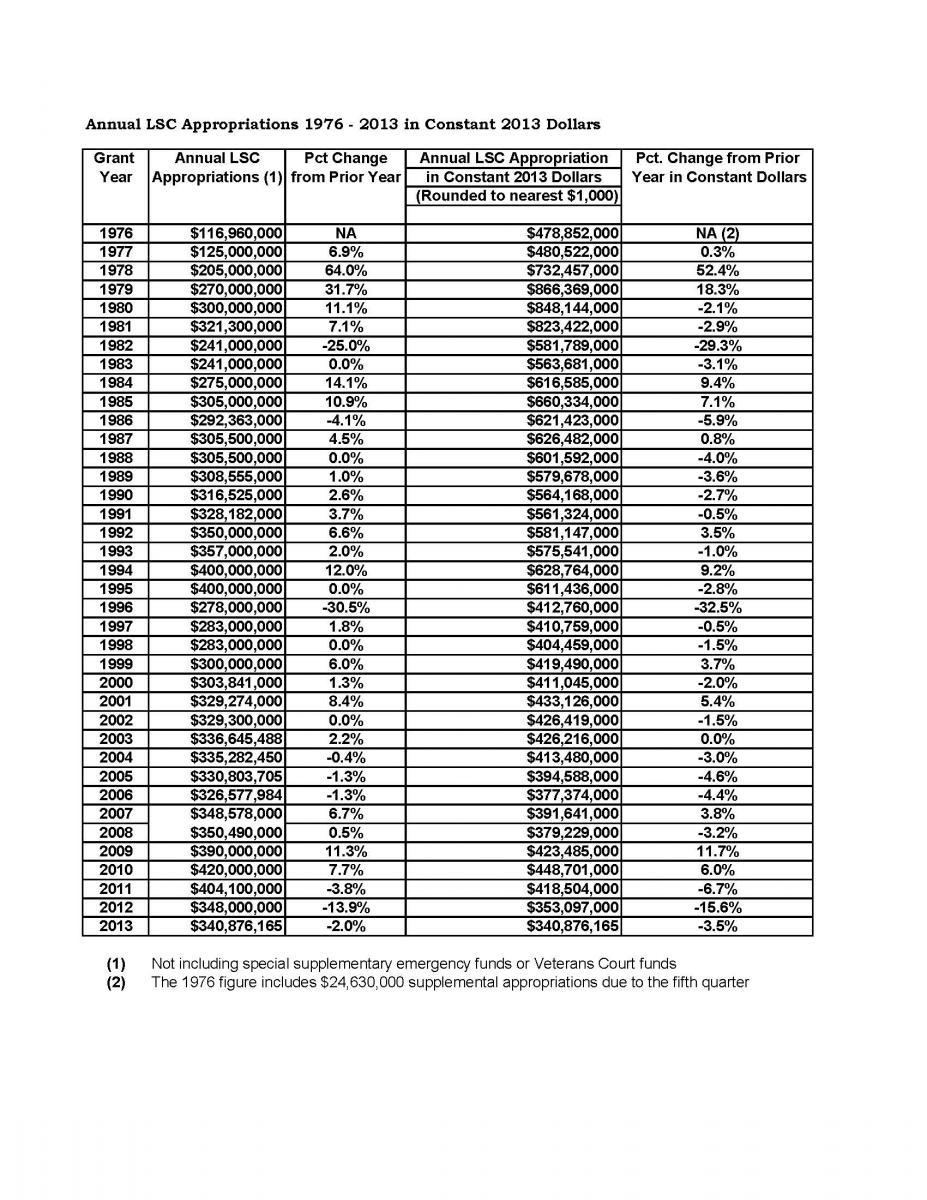

Because of shrinking resources, legal aid programs have had to reduce the type of assistance they provide to clients. Fifty-two percent of LSC’s funding recipients reported that in 2013 they changed case-acceptance policies, narrowed program priorities, or implemented similar measures that adversely affected client services.17 LSC-funded programs reported that they implemented one or more of the following changes in 2013:18

30% of LSC grantees reduced services by lowering income- eligibility limits, restricting overall case-acceptance standards, eliminating practice areas, or prioritizing cases with a high likelihood of success.

24% reduced the number of cases in which they provided extended representation.

39% reduced family law cases, such as eliminating specific types of cases (for example, contested divorces, custody).

27% reduced services to victims of domestic violence, for example, restricting services to cases where the victim had children, eliminating services in particular jurisdictions or not accepting referrals from outside agencies, limiting representation to securing protective orders, or restricting representation to emergency circumstances or the “most egregious fact patterns.”

22% reduced representation in housing matters, for example, evictions and foreclosures.

21% reduced services in consumer cases, for example, bankruptcy, predatory lending, or consumer debt.

State studies consistently show that only twenty percent of the civil legal needs of the eligible population are being met. For example, a recent study by the Boston Bar Association found that in Massachusetts civil legal aid programs turn away 64% of eligible cases.19 Nearly 33,000 low-income residents in Massachusetts were denied the aid of a lawyer in life-essential matters involving eviction, foreclosure, and family law such as cases involving child abuse and domestic violence.20 People seeking assistance with family law cases were turned away 80% of the time.21

New York’s recent findings confirm national data that fewer than twenty percent of all civil legal needs of low-income families and individuals are met. In 2013, more than 1.8 million litigants were not represented by counsel in civil proceedings in New York’s state courts.22 In New York City, 91% of petitioners and 92% of respondents do not have lawyers in child support matters in family court, and 99% of tenants are unrepresented in eviction proceedings.23 In New York State, 87% of petitioners and 86% of respondents do not have lawyers in child support matters in family court, and 91% of tenants are unrepresented in eviction proceedings.24 These enormous volumes of unrepresented litigants in our Nation’s courts fundamentally undermine the justice available to those litigants as well as to other parties whose cases are delayed because of the time required to fairly address cases involving unrepresented parties.25